Glasseye

Issue 16: August 2025

In this month’s issue:

Semi-supervised offers some advice to the tongue-tied frequentist

Synthetic populations - the latest synthetic bullshit to find its way onto the dunghill

The white stuff asks whether humans still have the edge when it comes to good quality prose.

Plus an abortive retreat into spacemacs, talking to the dead, and some experimental vibes.

Semi-supervised

One of the first things we learn (and perhaps the last we understand) in any introductory statistics course is that a confidence interval is not to be understood as a range that contains the population parameter with a given probability. While it’s nice to know what a confidence interval is not, most people, and more pointedly most employers, would like to know what it is. And, what’s worse, they expect this to be explained in no more than two or three sentences.

This is the dilemma I’d like to help you with today. What is the best wording to explain something you know to be fiendishly counterintuitive, for an audience with zero interest in the philosophy of probability?

(And yes it’s a trap we all escape by going Bayesian. But the most die-hard of Bayesians still has to live in a world in which their boss or client is more likely to be familiar with confidence intervals than credible intervals. At a minimum they would like to see you explain the former before they buy the latter.)

So first a very quick, since it is explained ad nauseam on the web, recap of why interpreting a confidence interval is difficult in the first place. For a frequentist, a probability is a property of a series of experiments. It is the frequency at which a given event occurs during these experiments, or, more precisely, the limit approached by that frequency as the number of experiments tends to infinity. This severely limits the kind of thing that can have a probability. Single experiments cannot have a probability. A finite group of experiments cannot have a probability. Thus, from a frequentist perspective, it is nonsense to talk about the probability of obtaining a six in a single die roll. Only a potentially infinite series of such rolls has a probability.

The drawing of the sample used to build a confidence interval counts as a single experiment. Whether or not the resulting confidence interval contains the population parameter is a single event, like getting a six with a single die roll. Therefore, it is not the kind of thing that, according to the frequentist, can have a probability. What can have a probability is the event that the confidence interval contains the population parameter when the sampling and confidence interval calculation are endlessly repeated. Why? Because then it can have a frequency, and that frequency can have a limit.

Hence to the frequentist, the otherwise very fair-sounding question: “What is the probability that the range you have just given me contains the true value?” is simply nonsense, alongside “What is the probability that it will rain tomorrow?” or “What is the probability that the next card is the king of spades?” The correct response is an eye roll.

How did the founders of frequentist statistics get away with such an extraordinary cop out? How did they avoid the flak we’d now get if we even attempted to pull this off? Part of the explanation is the intellectual climate in Europe in the early part of the nineteenth century. This was a period in which people took seriously the idea of creating a grounded, rigorous scientific language that was quite separate from the language of ordinary people. The frequentists were co-opting the term “probability” for this language. Ordinary people could still make primal grunting sounds that vaguely indicated degrees of belief (just as they could make them in appreciation of artworks or ethical positions) but this was not the precisely defined thing that now went by the name of probability.

So this is the core of the dilemma: because it is so widely adopted, we can’t abandon the tool that we have inherited, but neither can we adopt the methodologically correct position with respect to its use - i.e. blink a lot and claim not to understand the question. Are there no words that can get us out of this?

If you look through the textbooks and the literature, what mostly happens is that probability sneaks back into the interpretation of the confidence interval through phrases such as “likely to be” or “plausible range of values”. This is unsurprising: the frequentist might have run off with the word “probability” but we still need to somehow express degrees of belief. Hence we lean on the remaining probabilistic terms. My preferred wording is still guilty of this to some extent, but I think gets across, by its connotations, the proper frequentist position. Here it is:

The population parameter is between x and y. The technique we are using to provide this range is reliable. It is right 95% of the time.

I like this wording because it separates the claim, ”the population parameter is between x and y” about which - keeping the frequentist happy - nothing probabilistic is being said, from the reliability of the technique, which, as a series of repeated experiments, can be given a probability. It thus encourages the reader to make the right kind of inference - along the lines of “Will this car break down? … I don’t know but this make of car is very reliable.”

Many thanks to Adrià Luz, whose deceptively simple question about presenting confidence intervals led to this post.

Please do send me your questions and work dilemmas. You can DM me on substack or email me at simon@coppelia.io.

The white stuff

I have a theory, actually more of a hope, that LLM-generated prose is not the end of journalism and other kinds of professional writing, but a revitalising force - faced with an inferior and untrustworthy alternative, consumers will once again see the value of good, well-researched prose, and be willing to pay for it. Naive? Luckily I can check my armchair theories with an industry expert. If you have not already subscribed to Chris Duncan’s substack on the intersection of copyright law, media industry, and AI then I urge you to do so. It’s the good prose I’m talking about.

When I expressed my hopes to Chris, he was less optimistic, pointing out that “it is equally likely that the impact [of the proliferation of AI generated content] is for consumers to mistrust all information equally - same thing happened to politicians during the expenses scandal, where one party sinned and all parties suffered.” But Chris did agree that “the real opportunity for publishers is to spend marketing money to show that they are run by humans who are on your side, and that there is a human touch to original sources that gets diluted by machine abstraction.”

The idea of there being a “human touch to original sources” prompted a dive into the latest research comparing AI-generated and human-generated text. Here are a couple of interesting papers. Differentiating between human-written and AI-generated texts using linguistic features automatically extracted from an online computational tool by Georgios P. Georgiou takes a statistical approach to uncovering the differences. Aside from making me very curious about the nature of approximants, fricatives, laterals, nasals, and plosives, it was helpful for confirming what most of us already feel: AI-generated content is different but in subtle ways. The paper cites previous work showing that there is less variation in sentence structure in AI-generated text:

AI-generated essays exhibited a high degree of structural uniformity, exemplified by identical introductions to concluding sections across all ChatGPT essays. Furthermore, initial sentences in each essay tended to start with a generalized statement using key concepts from the essay topics, reflecting a structured approach typical of argumentative essays.

Georgiou’s study adds to these findings by spelling out the structural differences: “the AI text used more coordinating conjunctions, nouns, and pronouns, while the human text used more adpositions, auxiliaries, and verbs.”

A second paper AI vs. Human - Differentiation Analysis of Scientific Content Generation by Ma et al comes to a similar conclusion, but rather than using statistical analysis to analyse differences it (among other things) examines the features used by the RoBERTa-based OpenAI Detector to differentiate GPT content from human text. The paper is a little old so I wondered about the current state of AI content detectors. This in turn led me to something I can barely get my head around - the use of such detectors to identify passages in AI-generated content that look too obviously like they were generated by AI, so that humans can tweak them by adding a human touch. Grammarly is explicit about this use case for their detection tool “Grammarly’s AI content detector and writing assistant assess your work for you, so you know exactly where to refine and polish to make sure it’s authentically yours.” To see how this is actually being used, check out this quote from an American high school student reported in The Important Work (which I came across in Cognitive Resonance):

For me, William, and my classmates, there’s neither moral hand-wringing nor curiosity about AI as a novelty or a learning aid. For us, it’s simply a tool that enables us not to have to think for ourselves. We don’t care when our teachers tell us to be ethical or mindful with generative AI like ChatGPT. We don’t think twice about feeding it entire assignments and plugging its AI slop into AI humanizing tools before checking the outcome with myriad AI detectors to make sure teachers can’t catch us. Handwritten assignments? We’ll happily transcribe AI output onto physical paper.

Last year, my science teacher did a “responsible AI use” lecture in preparation for a multiweek take-home paper. We were told to “use it as a tool” and “thinking partner.” As I glanced around the classroom, I saw that many students had already generated entire drafts before our teacher had finished going over the rubric.

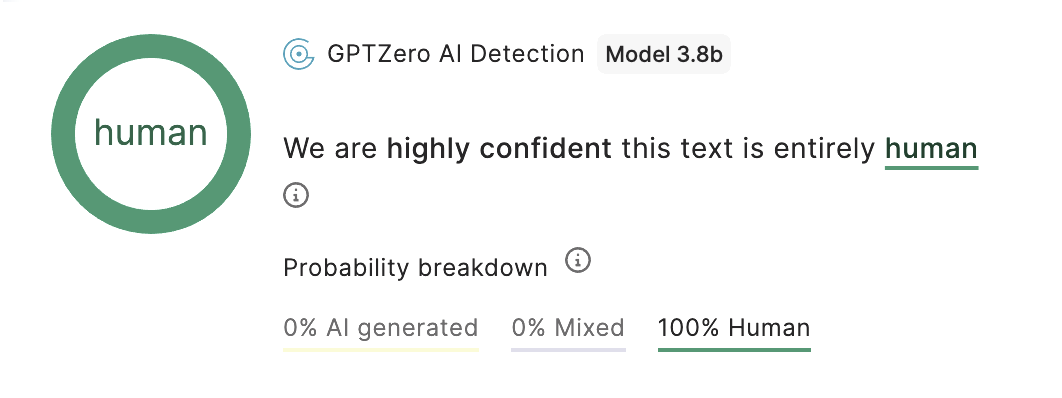

A better use of these tools is to reassure yourself that you are, in fact, human. I fed the above into GPTZero (another detector) and I am pleased to report that …

P.S. For a fun activity try submitting the Campaign article mentioned in the Dunghill into the same detector.

The dunghill

It certainly feels like ‘agentic’ and ‘synthetic’ are the bullshit terms of the moment. Bullshit evolves, so perhaps it is significant that they are sly little adjectives and not the hefty nouns we’ve grown wary of (compare ‘big data’, ‘block-chain’, and ‘AI’ itself).

Let’s leave ‘agentic’ for another time. It’s too slippery and frankly too irritating. ‘Synthetic’ we’ve seen several times already: synthetic respondents, the boosting of sample sizes with synthetic data. All good things come in threes, so it’s no surprise that Scott Thompson has dug out another one for me - synthetic populations.

Unfortunately, the article he found, Synthetic populations could be the future of media planning, is behind a paywall. This might be for your own protection. As Scott pointed out to me, there are so many things wrong here that it is difficult to know where to start.

But start we must, so I’ll begin with this: I can see here a move very common to AI-related bullshit. This is to slip between, on the one hand, well-established, sometimes decades-old techniques, and, on the other, highly speculative, unproven or nonsensical ideas, and to do this as though they were the same thing. This works because if you want concrete examples of successful applications of the technology then you fall back on the former; if you want to wax futuristic you glide back to the latter. Sometimes this is done cynically, in full knowledge that two are in fact different; at other times it is done in ignorance. (A classic example can be seen in the way that successive British governments have promoted their plans for AI within the NHS. When they want to talk up its successes, they refer to the use of AI in screening and scanning - old school machine learning no doubt, but talked about as though it were one and the same with new school generative AI, whose successes have yet to be seen.)

Synthetic populations is just this again. The old school tech is agent-based modelling, the dubious parvenu is of course the whisker-twiddling LLM. Let me talk you through it.

The article begins in full-on prophetic mode:

As media planning moves into an era shaped by privacy, AI, and unpredictability, a radical new concept is poised to redefine how we think about audiences: synthetic populations. These virtual societies, built from real-world data and fuelled by machine learning, could give marketers the ability to simulate campaigns before they ever go live.

Synthetic populations are not new. They have been around for decades as an essential component of agent-based modelling (a simulation technique that involves modelling the interactions between agents whose characteristics are distributed to mirror real-world populations). And the idea of using agent-based modelling to “simulate campaigns before they ever go live” is just as old. So perhaps the author means something different? Let’s look at some of his ambitions for synthetic populations:

Rather than extrapolating from panels or historical data, synthetic populations offer a proactive approach. Planners can model out-of-home exposure, simulate podcast engagement, or test social creative across varied personas and life stages.

Want to understand how a price-sensitive household in the Midlands might respond to a supermarket ad during an economic downturn? Or if a premium beauty product resonates more in urban rentals than suburban family homes? These are scenarios synthetic models could answer – before a campaign goes live.

Now admittedly an agent-based model is going to struggle to do any of this. Their strong suit is in helping us understand the behaviour of systems which, because of feedback loops and complex interactions, are too difficult to understand without simulation. If we want to understand the effect of a premium beauty product using an ABM then we must provide data about these beauty products and specify rules about how people behave towards them, given their demographic profiles. But the implication of the above is that any impromptu query can be fired at the synthetic population.

So what is being sold here under the banner of synthetic populations? Well it’s not explicitly mentioned but I think we can all guess: the plan is for agents to be driven by LLMs, that is they will make decisions based on prompts that specify their individual profiles and backgrounds, as well as the details of the decision.

Everything that is wrong about synthetic respondents in survey panels, as detailed in previous posts is just as wrong here. We have no idea how the LLM training data relates to the population we are simulating. We might think we can overcome this by comparing the behaviour of our simulated populations with real data, but the broad patterns used in such comparisons are rarely the ones that people are interested in. (As the quote above shows, synthetic populations are being sold as way of answering very specific questions, and there’s no way of ensuring algorithmic fidelity on these points without conducting your own real world research - at which point why would you need the synthetic population?)

But credit where credit is due - the article does at least present a theory that is falsifiable. In fact, better than that, it contains, to use Popper’s language, bold, novel predictions. Take the one mentioned above: in the near future we will be able to successfully predict how a price-sensitive household in the Midlands will respond to a supermarket ad during an economic downturn. Not just the average price-sensitive Midlands household mind - this will be specific “household level insight”. Now that’s bold.

ABMs were never great at predictions: too many assumptions were needed, and too many models with very different outcomes fit the available data - but at least we knew what the assumptions were. My prediction about the future of campaign planning is considerably less bold. I think such synthetic populations, if they ever come to be, will be awful predictors of campaign performance. I also predict that, given the millions of hidden assumptions, we will have no idea why.

If you have some particularly noxious bullshit that you would like to share then I’d love to hear from you. DM me on substack or email me at simon@coppelia.io.

From Coppelia

As I think I mentioned before, in uncertain times I feel an irrational pull back to the terminal and the command line. I don’t think I’m alone in this. It’s probably a need for total control mixed with 80s nostalgia. Anyway, I’ve always been a vim guy and never really looked at emacs. However this month I discovered spacemacs, the Emacs advanced Kit focused on Evil. Which sounds amazing, however you may be disappointed to find that EVIL stands for extensible vi layer for Emacs, which means I can use my vim bindings while taking advantage of the many emacs extensions. It’s a wonderful thing to see your email inbox in a text editor. The moment of fear and paranoia has passed, however, and it might be a while before I revisit it.

Thank you to Mark Bulling for taking me through his pragmatic, realist approach to vibe coding. It was the perfect corrective to all the evangelistic stuff I’m seeing online. Perhaps more on this next month.

A truly weird variant of the synthetic respondent idea appeared in the Newsagents this month. “Reflekta, allows people to create digital versions of deceased relatives by feeding the system memories, text, and voice recordings, enabling ongoing conversations for a monthly subscription fee.” This is no more your grandad than the synthetic panellist is a billionaire tech bro. But it’s a lot sicker (Pet Sematary vibes) and feels more like a kidnapping. Pay or grandpa gets it (although he’s actually already had it.) Please stop.

If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter or have any other feedback, please leave a comment.

Some interesting topics! I think most online models (e.g. ChatGPT) are fairly detectable because we specifically train them not to respond like normal humans, e.g. in the finetuning / RLHF steps, and we also almost never sample from the probability distributions completely randomly (I.e. temperature = 1, top_p = 1)

I did quite a bit of research in this area a couple of years ago (admittedly a bit out of date now) but I think if you took a large base model without fine-tuning steps, and sampled from the softmax completely randomly, a lot of these measured stylistic differences might dissappear (especially around lower variation and word choice). Although I guess most people are probably just using default ChatGPT model and settings so perhaps we don't need to worry too much!

It was a literature review primarily, so I only did small amounts of playing around with building detectors myself, but did read almost all the literature that was around then. Most studies were using ChatGPT output or similar so will have included the fine-tuning RLHF bits, but most didn't go in to much detail in to their dataset creation and didn't compare models so no particularly robust results.

Yeah I also suspect we prefer some kind of simplicity, which is reinforced by the RLHF and fine-tuning steps. But no evidence to support this.

Yeah good question. I would suspect it's just a slightly dodgy black box detector that was trained on a limited dataset? So works fairly well generally, but occasionally the probabilities are wildly wrong for models / topics / writing styles that are not part of the training data (at least that was the case 2 years ago). Must be almost impossible to get a complete like-for-like human / AI dataset with all possible styles, models, sampling parameters etc.